- Common Ground

- Posts

- Cracking the Congress Code

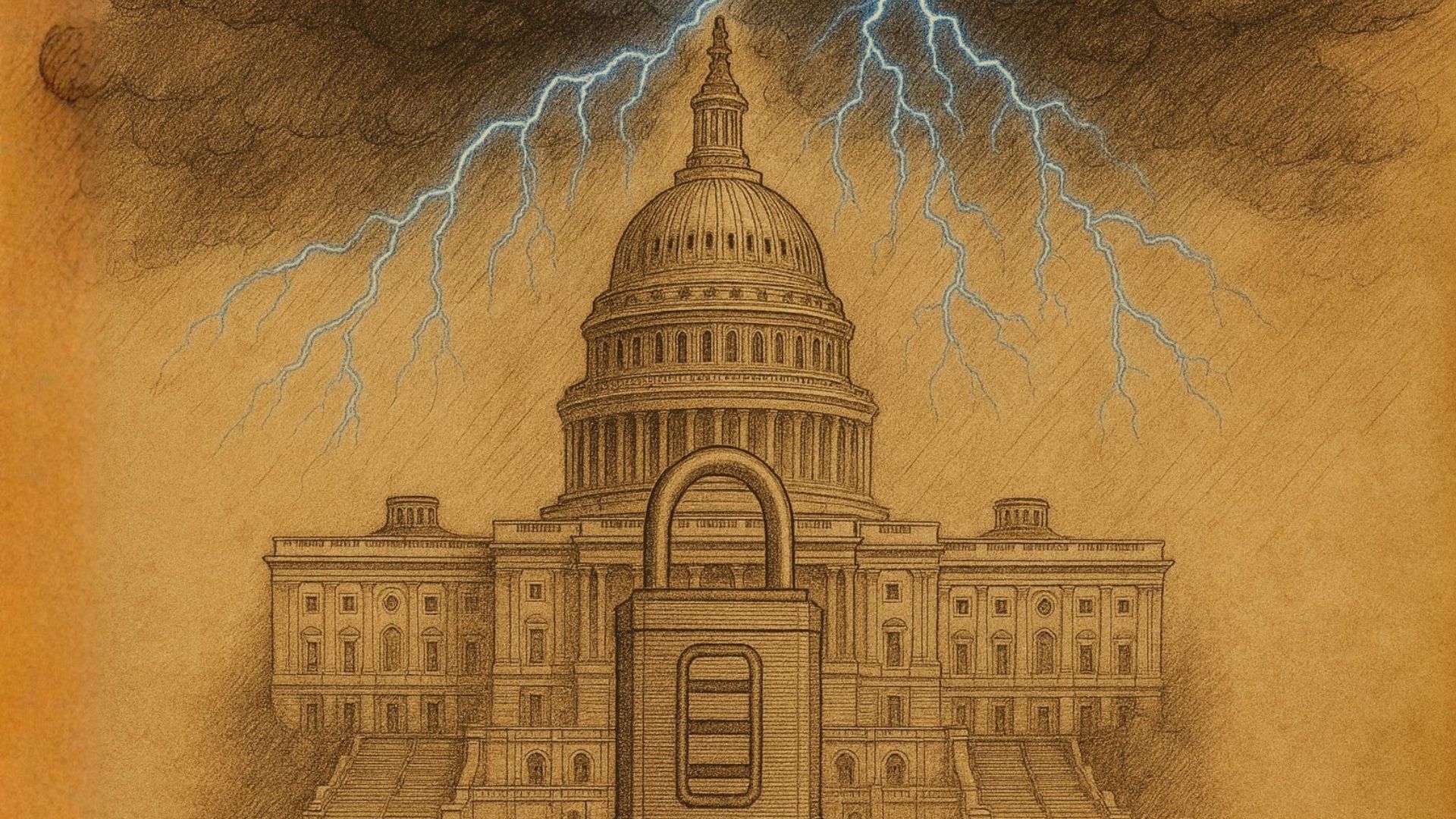

Cracking the Congress Code

How collision, not consensus, shapes America's laws.

Most Americans sense it before they can explain it.

Legislation often moves slowly. Painfully. Months turn into years. Popular ideas stall. Urgent problems linger. When laws do finally emerge, they feel bloated, incoherent, or oddly disconnected from what anyone remembers asking for. The natural conclusion is that nothing is getting done, or even worse, that something is deeply broken.

But what if the problem isn’t that Congress fails to act?

What if the problem is that we misunderstand what Congress was designed to produce?

Contrary to popular belief, Congress does not operate like a popular vote or a marketplace of ideas. It does not aggregate preferences and deliver outcomes proportional to public demand. It operates more like a collision — a place where competing interests are forced together under immense institutional pressure, and where the final result is not chosen, but what survives.

In the universe, when two neutron stars collide, they do not merge cleanly. The impact is violent, constrained by gravity so intense it bends space itself. Most matter is destroyed. What remains is not what either star was before — it is a byproduct of collision: radiation, shockwaves, and rare elements forged under pressure. No one designs the outcome. It emerges.

Congress works the same way.

The father of the Bill of Rights, James Madison himself, understood this. In Federalist No. 10, he wrote that “the regulation of these various and interfering interests forms the principal task of modern legislation.” Not agreement. Not efficiency, but regulation through interference. Through friction.

Once you see Congress this way, its behavior becomes less mysterious. The delays. The compromises. The strange provisions no one seems to defend. These are not accidents. They are the residue of institutional collision — the unavoidable discharge of a system designed to restrain power, not express it cleanly.

This essay is an attempt to crack that code. To pull back the veil and explain what Congress actually does, why it feels so disconnected from public expectation, and why outrage alone cannot fix it. More importantly, it asks a harder question: if polarization and corruption are symptoms of misaligned incentives, what would it take to realign them and allow a new American enlightenment to emerge, not through domination, but through understanding.

After reading Madison, one will realize that he never imagined Congress as a machine for translating majority opinion into law. Evidence for this in addition to his ideas on “various and interfering interests,” are his words in Federalist No. 51, where he explains that ambition itself must be used as a counterweight. In his view, Congress was designed not to choose outcomes, but to subject competing forces to institutional pressure until only certain outcomes survived. The strange, compromised, and often frustrating laws we get are not accidents… they are the residue of that collision.

I recognize that in late 2025, dismissing the thoughts and ideals of the Founders is in vogue. However, I contend that by doing so, we not only handicap ourselves from understanding the operational design of our legislative branch — the very machine through which We the People enact change — but also overlook what I call the Great Realization.

That realization is this: we love to critique the very system the Founders created because of their historical flaws and moral shortcomings, despite the fact that the very system they built allowed us, over time, to correct the very flaws we hate them for. In the end, that capacity for self-correction was not incidental — it was the point all along: a system of self-governance, self-correction, collision, friction, freedom, and beauty… if we can keep it.